Vintage Philippine literary and movie magazines are rich references for identifying komiks serials that had been made into the movies.

Vintage Philippine literary and movie magazines are rich references for identifying komiks serials that had been made into the movies.I am very fortunate to acquire a good number of these old magazines from the 1920s to the 1950s, a rich minefield of information about our rich comics and movie heritage. Reading these vintage magazines provides me with the feeling of travelling through a Time Machine wherin I could get a glimpse of the olden days even decades before I was born.

My project on "Komiks and the Movies" is really getting exciting as I unearth more rare materials long since been considered extinct. As a komiks and magazine collector, I know how difficult it is to find these materials. Yet, through the years, I have not stopped hunting them in antique shops, Ebay auctions, flea markets, etc. Right now, I have more than 2,000 pieces of old Tagalog komiks and original comic art, and some 300 vintage magazines/songhits.

To my knowledge, there is no existing komiks library or gallery of comics and original comic art in the Philippines, or indeed anywhere else in the world. The National Library formerly has a good number of bound tomes of old komiks donated to them by Lope K. Santos, but all of these(save a two or three tomes) have mysteriously disappeared from their shelves.

The remaining two or three tomes are either in bad condition or very bad condition, with several pages torn or missing. It seemed that librarians have a discrimination towards comics, and they tend to treat it as reading materials "without research value". I found otherwise, reading komiks gives me a profound and unique look on Philippine culture I would not normally find on some boring textbooks.

Anyway, here are some more new finds for my project "komiks and the Movies". I will only concentrate on the Golden years of Philippine comics which, incidentally also coincides with the Golden years of Philippine movies (roughly the years 1947-72). It seemed that the fall of the komiks industry also advresely hurt the Philippine movie industry. I hope that this humble project finds itself in a pictorial book that is currently gestating in my mind.

Goldiger by Dominador Ad Castillo and Nestor Redondo. Serialized in the Manila Klasiks 1953

Goldiger by Dominador Ad Castillo and Nestor Redondo. Serialized in the Manila Klasiks 1953

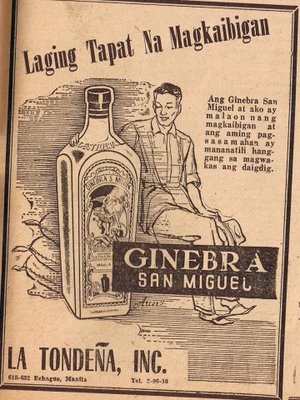

Oops, before we continue, let's give way to a little commercial from Ginebra San Miguel. The man on the ad says:"Ang Ginebra San Miguel at ako ay malaon ng magkaibigan, at ang aming pagsasamahan ay mananatili hanggang sa wakas ng panahon". Hehe Lasenggo pala ito.

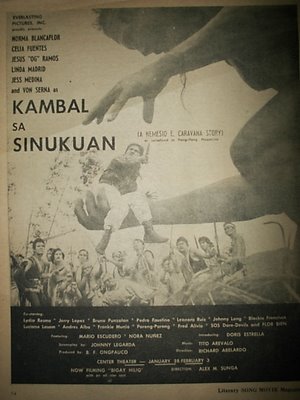

Oops, before we continue, let's give way to a little commercial from Ginebra San Miguel. The man on the ad says:"Ang Ginebra San Miguel at ako ay malaon ng magkaibigan, at ang aming pagsasamahan ay mananatili hanggang sa wakas ng panahon". Hehe Lasenggo pala ito. Nemesio Caravana's Kambal sa Sinukuan. Serialized in the comics section of Ilang-Ilang Magazine 1951

Nemesio Caravana's Kambal sa Sinukuan. Serialized in the comics section of Ilang-Ilang Magazine 1951

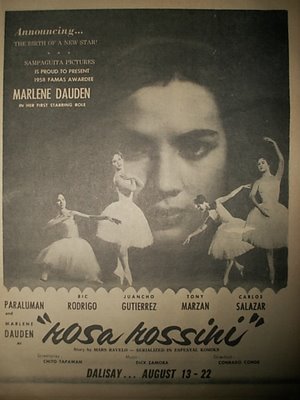

Rosa Rossini by Mars Ravelo. Serialized in the Espesyal Komiks, 1959

Rosa Rossini by Mars Ravelo. Serialized in the Espesyal Komiks, 1959

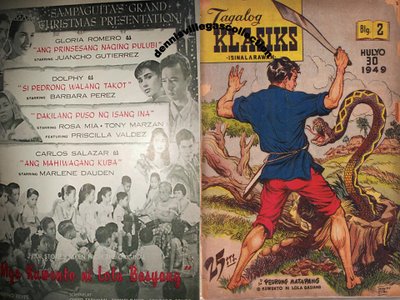

Severino Reyes' Mga Kwento ni Lola Basyang first appeared as prose fiction in the Liwayway in 1923. These wonderful stories were later adapted into comics by Severino Reyes' son, Pedrito Reyes, in the Tagalog Klasiks Komiks.

Severino Reyes' Mga Kwento ni Lola Basyang first appeared as prose fiction in the Liwayway in 1923. These wonderful stories were later adapted into comics by Severino Reyes' son, Pedrito Reyes, in the Tagalog Klasiks Komiks.

A commercial from our sponsor, Omega watches. Only 22 pesos in 1923. From the Lipang Kalabaw magazine 1923. Call La Estrella del Norte department store at tel #250 or #251. Offer is good while supplies last. Magkano kaya ang buong tindahan ng La Estrella del Norte noon, gusto ko ng bilhin e sa sobrang mura.

A commercial from our sponsor, Omega watches. Only 22 pesos in 1923. From the Lipang Kalabaw magazine 1923. Call La Estrella del Norte department store at tel #250 or #251. Offer is good while supplies last. Magkano kaya ang buong tindahan ng La Estrella del Norte noon, gusto ko ng bilhin e sa sobrang mura.

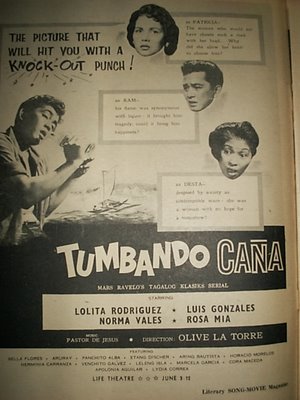

Tumbando Cana by Mars Ravelo. Serialized in the Tagalog Klasiks Komiks, 1956

Tumbando Cana by Mars Ravelo. Serialized in the Tagalog Klasiks Komiks, 1956

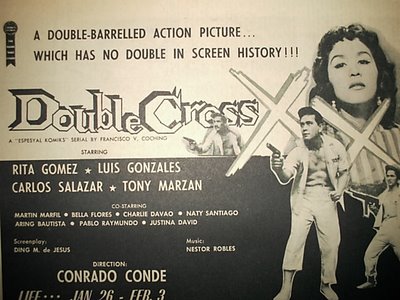

Double-Cross by Francisco V. Coching. Serialized in the Espesyal Komiks, 1956.

Double-Cross by Francisco V. Coching. Serialized in the Espesyal Komiks, 1956.

Another advertisement, this time from the old reliable Alhambra Regaliz Mahaba. This cigarillo is a favorite of old women in the provinces who smoke it with the burning end inside their mouths while chewing Nga-nga or playing tong-its, hehe. Only 30 centavos per pack in 1954.

Another advertisement, this time from the old reliable Alhambra Regaliz Mahaba. This cigarillo is a favorite of old women in the provinces who smoke it with the burning end inside their mouths while chewing Nga-nga or playing tong-its, hehe. Only 30 centavos per pack in 1954.

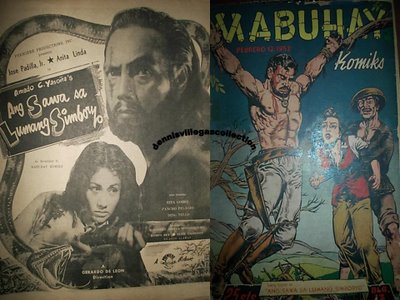

Sawa sa Lumang Simboryo by Amado Yasona and Hugo Yonzon. Serialized in the Mabuhay Komiks 1952. This movie received the first ever FAMAS Best Picture Award in 1952.

Sawa sa Lumang Simboryo by Amado Yasona and Hugo Yonzon. Serialized in the Mabuhay Komiks 1952. This movie received the first ever FAMAS Best Picture Award in 1952.

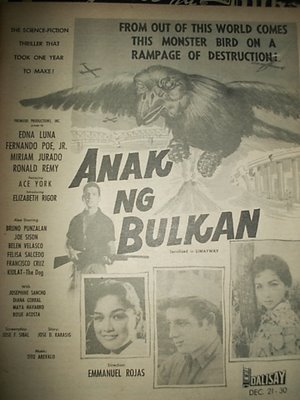

Anak ng Bulkan by Jose Domingo Karasig. Serialized in the comics section of the Liwayway, 1959. I have watched this movie several times during its reruns in Channel 5 on afternoon weekends. Starring Fernando Poe Jr. Poignant story of a little boy's friendship with a gentle giant bird. The little boy was Ace Vergel as a kid.

Anak ng Bulkan by Jose Domingo Karasig. Serialized in the comics section of the Liwayway, 1959. I have watched this movie several times during its reruns in Channel 5 on afternoon weekends. Starring Fernando Poe Jr. Poignant story of a little boy's friendship with a gentle giant bird. The little boy was Ace Vergel as a kid.

This cartoon escaped the supposedly keen eye of the Japanese military censors. By using an analogy to a captive bird, this cartoon plainly stated the Filipinos' desire for freedom. Had the Japanese noticed this, Velasquez would surely have been incarcerated in the Fort santiago.

This cartoon escaped the supposedly keen eye of the Japanese military censors. By using an analogy to a captive bird, this cartoon plainly stated the Filipinos' desire for freedom. Had the Japanese noticed this, Velasquez would surely have been incarcerated in the Fort santiago. The complete originals of the Kalibapi Family that were published in the Japanese-controlled Tribune newspaper. Author's collection.

The complete originals of the Kalibapi Family that were published in the Japanese-controlled Tribune newspaper. Author's collection.

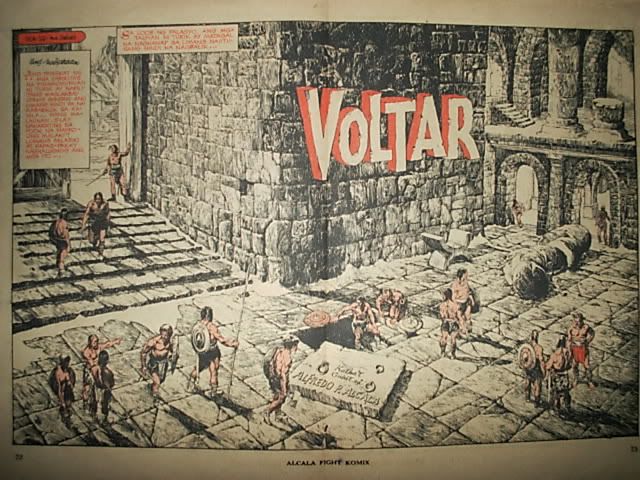

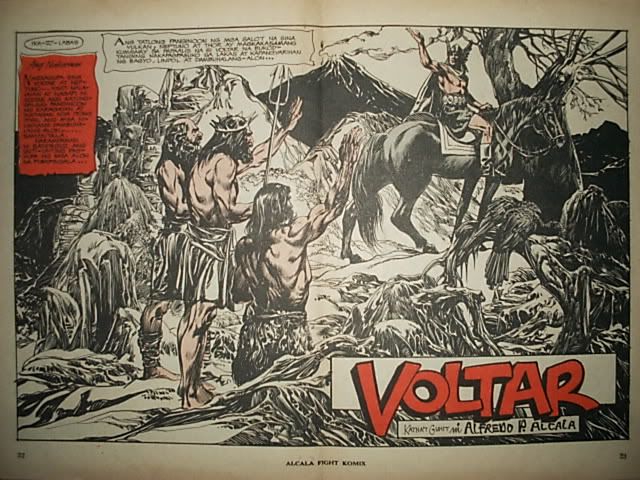

A gift from Mr. Manuel Auad, publisher of Auad Publishing. Thanks so much Noli!

A gift from Mr. Manuel Auad, publisher of Auad Publishing. Thanks so much Noli!

Ifugao by Cirio H. Santiago and Alfredo Alcala. Serialized in the Hiwaga Komiks 1956.

Ifugao by Cirio H. Santiago and Alfredo Alcala. Serialized in the Hiwaga Komiks 1956. Ooops, just a little advertisement from our dear sponsor Pepsi-Cola. Only 15 centavos per bottle in 1949. Ang Lugod ko..Mabuhay! Hehe

Ooops, just a little advertisement from our dear sponsor Pepsi-Cola. Only 15 centavos per bottle in 1949. Ang Lugod ko..Mabuhay! Hehe

Another commercial, this time from our dear sponsor Lifebuoy, the soap of the stars! 1955

Another commercial, this time from our dear sponsor Lifebuoy, the soap of the stars! 1955

Time out for a little advertisement from our friendly sponsor, Cashmere Bouquet. Only 25 centavos in 1954.

Time out for a little advertisement from our friendly sponsor, Cashmere Bouquet. Only 25 centavos in 1954. Asintado by Clodualdo del Mundo and Fred Carrillo. Espesyal Komiks 1958

Asintado by Clodualdo del Mundo and Fred Carrillo. Espesyal Komiks 1958  Vintage Magazines from the 1940s and the 1950s.

Vintage Magazines from the 1940s and the 1950s.  Page 1

Page 1 Page 2

Page 2 Page 3

Page 3  Page 4

Page 4 Page 5

Page 5

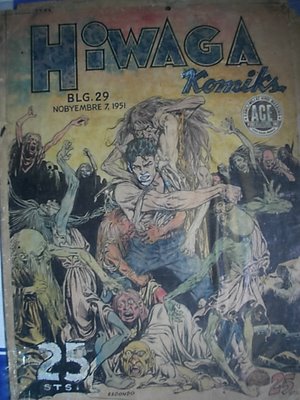

Original cover art of Hiwaga Komiks #29 by Nestor Redondo, for the graphic serial "Raul Roldan", written by Mars Ravelo. From the author's collection.

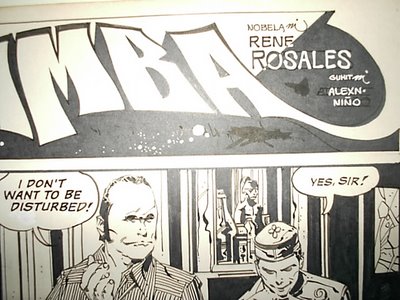

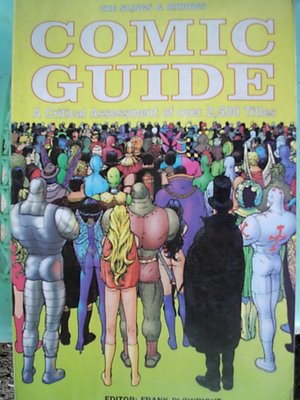

Original cover art of Hiwaga Komiks #29 by Nestor Redondo, for the graphic serial "Raul Roldan", written by Mars Ravelo. From the author's collection. The Comic Guide, edited by Frank Plowright. A critical refrence guide to collectable comics.

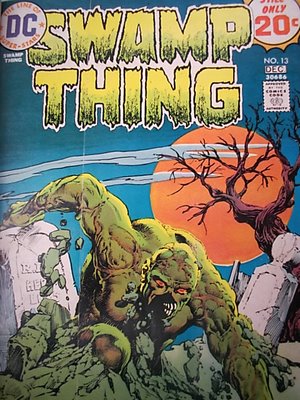

The Comic Guide, edited by Frank Plowright. A critical refrence guide to collectable comics. Cover: Swamp Thing #13, Nestor Redondo

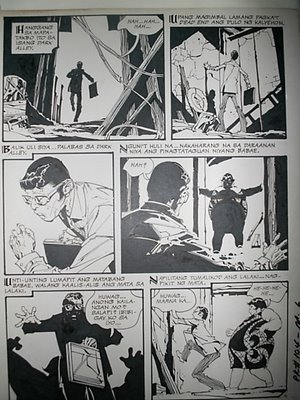

Cover: Swamp Thing #13, Nestor Redondo A panel page from Rima the Jungle Girl. The series lasted seven issues.

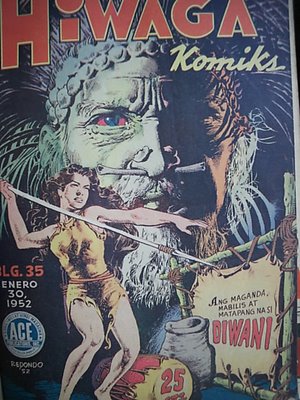

A panel page from Rima the Jungle Girl. The series lasted seven issues. Diwani, the first jungle-girl created by Nestor and Virgilio Redondo in the Hiwaga Komiks.

Diwani, the first jungle-girl created by Nestor and Virgilio Redondo in the Hiwaga Komiks. Another cover by Redondo in Hiwaga Komiks #35 for the popular Diwani serial.

Another cover by Redondo in Hiwaga Komiks #35 for the popular Diwani serial.